When folks write about Rayne Fisher-Quann there’s an unfortunate tendency to skirt the specifics of what she says and focus instead on her age (21), the means by which she communicates (SubStack, TikTok), the size of her audience/readership (many, many, many thousands), and the broad topics that she addresses in her cultural critiques (contemporary femininity, capitalism, and technology). Delia Cai, in her profile of RFQ for Vanity Fair, confesses that it might be that “we still can’t separate the platform from the substance of the work.” It’s unclear who Cai means by “we” here or why distinguishing between the substance of RFQ’s ideas from the platforms she uses to communicate them would pose any special problem. We - whoever “we” is - do not have trouble distinguishing between Malcolm Harris’ ideas and the fact that he uses articles, books, and podcasts to get those ideas out.

This peculiar tendency to favor all the minutia of RFQ’s life, looks, and online presence over and above her actual ideas is especially unfortunate because it falls entirely in line with and confirms her critique of how women (or, as she often prefers to emphasize, girls) are treated online, namely, as an assemblage of reified traits to be gawked at, manipulated, interrogated, and cast off as quickly as picked up. The very cultural practices she critiques throughout her work are visited on her again and again which must be both validating (her critiques get things right) and maddening (her critiques have not yet dissuaded people from these kinds of attitudes or behaviors). As Vonnegut, one of RFQ’s stated influences, would say: so it goes.

Hopefully, though, not for much longer.

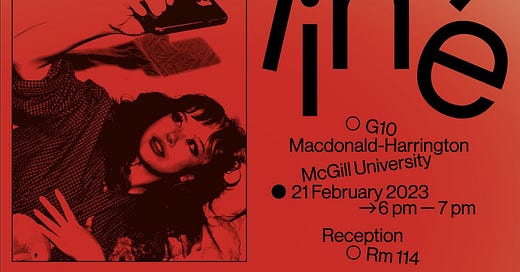

Last night, RFQ gave a talk - titled “girl online” - at McGill and, if nothing else, proved that people are here for what she has to say regardless of the means by which she says it.

Even though we showed up twenty minutes early (!), most of the 178 seats in room G10 of the (pretty on the outside, low-key unsettling on the inside) MacDonald Harrington building were already occupied. Rather than climbing over laps, we snagged a seat in the still empty front row and really hoped that it wasn’t secretly reserved for guests of honor (Emrata?!). Ten minutes later, the room must have been at capacity and yet people kept coming. Some perched on window sills, some sat in aisles, a few enterprising dudes dragged chairs in from an empty classroom and created their own makeshift rows. Nearing start time, a guy in a white button-down was turning people away continually. We had safely entered “fire hazard” territory.

The sheer number of people in attendance for RFQ’s inaugural talk would, by itself, be notable - but more surprising was, well, the vibe. People seemed excited. Even the people who saw upon entering the crowded room that there was no chance they’d get to sit with their friends seemed happy about it, pleased that this event had inspired this kind of turnout. This wasn’t Beychella - to be clear - but it felt like something significant before it even started. Starting, though, was a little fraught.

***

Because the gods are equal parts cruel and funny, RFQ’s “girl online” lecture got a late start because of tech issues. Men who were seemingly new to computers and projectors frantically tried to get things working for a while. At one point RFQ and her friend (?) tried to manually type in the nonsense string of letters and numbers in a GoogleDocs URL in an attempt to access her presentation. Eventually, a humble USB key saved the day.

These tech issues wouldn’t normally be worth mentioning due to how frustratingly common they are in academic settings (for real, there’s a reason a lot of profs still use CHALK in the year of our lord 2023), but there’s a sense in which these troubles with technology in the real world highlight one of the central ideas in RFQ’s work. In particular, we often fall into a habit of thinking that online and offline life are inextricable from each other or seamlessly conjoined. We mistake the aspirational and constructed fantasy of online experience with the really real stuff of day-to-day life. This, as she notes in various ways across her work, is a problem and it’s a problem we need to address critically. Not to put too fine a point on it, but we all - on RFQ’s view - struggle with tech problems, with rightly (and healthily) translating what we see and do online into the other and multiple aspects of our everyday lives. Tech problems do not, though, impede us from living nor, thankfully, did they hamper RFQ’s talk for very long.

Fifteen minutes after six o’clock, Samiha Meem - an architectural designer, writer, and instructor at McGill - addressed the audience to explain that this talk was part of a series of lectures hosted by McGill’s School of Architecture having to do with “Culture, Storytelling, and Image-Based Reality Construction.” After quickly citing Deleuze, David Shields, and bell hooks on the means and manner by which worlds are constructed and understood, Meem introduced RFQ and noted her various publications. RFQ graciously thanked Meem for the introduction and the audience for their patience, cued up a TikTok and (OK, fine, the video didn’t load right away and there was like a minute of extra fussing with things and she had to complete the puzzle piece captcha (much to everyone’s delight), but anyways really shortly after that other tech problem) the talk began.

***

The crux of RFQ’s argument in “girl online” is that a prevalent aspect of contemporary (Western) ideology falsely defines who a woman is by way of the objects she consumes. We can see this ideology play out most clearly by looking at lifestyle influencers like the English Country Grandmother or the It Girl. Lifestyle influencers, on RFQ’s account, do not portray an achievable lifestyle, but rather present a set of commodities that symbolize or otherwise stand for an nebulous variety of unactualizable fantasies or desires.

In support of her argument, RFQ relied largely on Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle - a canonical work of French critical theory - which, amongst other things, argues that “all of [contemporary] life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.” We live in a faux world, Debord proclaims, a spectacle “where the tangible world is replaced by a selection of images which exist above it, and which simultaneously impose themselves as the tangible par excellence.” For Debord, our relationships with each other and everything else are mediated and corrupted by this plethora of mere images, of spectacularized products, that are presented to us constantly and everywhere.

While Debord is cited, his work was not prominently featured or at all critiqued in RFQ’s talk. It seemed like it was used more than anything as a marker that many of the problems we find ourselves faced with are not particularly novel. The lifestyle influencer might be new on the scene, but the commodity fetishism enacted or embodied by them is not. What RFQ, instead, took to be a particularly new twist of this old knife is that the internet (and social media in particular) inspires or demands that women commodify themselves for the sake of the (attention) economy. While it may have once been the case that the subject under capitalism was like a stubborn donkey motivated by carrots (commodities) dangled forever out of reach, it is now the case that women in particular are both donkey and carrot. [The donkey/carrot analogy was RFQ’s, by the way, and not our editorialization.] One is caught in a perpetual cycle of desiring an unattainable something, of imperfectly turning oneself into the supposed object of desire, then repeating the cycle when it all fails to feel fulfilling or satisfying or good even at all.

After talking through the consumptive logic of online lifestyle influencers and the particular ways they rely or prey on women/girls as a vector, RFQ suggested that any and all participation in online life (particularly social media) entails objectification and self-commodification regardless of one’s individual identity markers. And on this fairly somber note, RFQ thanked us and the talk ended. Raucous applause followed.

***

From where we’re sitting, maybe the most interesting part of RFQ’s talk - and her work more broadly - lies in what she doesn’t do. She doesn’t trot out baggy quotes from primary or secondary sources. She doesn’t prop up her points by dismissing or attacking those of others. She doesn’t rely crutch-like on technical jargon or terms of art. She doesn’t use examples from distant history as if they were evergreen. She doesn’t suggest that she has identified the path to communal salvation. She doesn’t even - as she made very clear last night - want to negatively judge the very influencers that she takes to be problematic in the extreme.

The avoidance of all these customary aspects of cultural criticism might strike some as evidence of a kind of dilettantism, but the more generous and productive reading of these various refusals is that RFQ’s critical practice aims to speak to as many interested parties as possible about things they take to matter in the clearest of possible terms. Her aim - as far as we can see - is to essentially put up “Warning!” signs across the cultural landscape. Just as it would be misguided to criticize a “Warning!” sign for its choice of font or the means by which it is put up - so too would it be misguided to get hung up on the formal ways that RFQ’s criticism does not resemble what you might read in Critical Inquiry or The New Criterion.

It is hard, obviously, to identify why any particular person’s work succeeds in capturing broad attention, but at least one of the engines of RFQ’s appeal is that she speaks to her audience in a way that feels direct. This isn’t to say that she is offering up her authentic self or that she is performing authenticity expertly, but rather that she is delivering a set of complicated ethical and political messages that are unencumbered by the metric fuckton of pretension and condescension that typically accompany them. She is and cares about “girl[s] online,” so talks to and about and like “girl[s] online.” She does not pretend to be the first or the last word on the matters that concern her, but instead offers up insights that might simply help clarify (or productively complicate) the chaotic nightmarescape that we presently occupy together. Her work - no matter where or how it is delivered - is pointed, funny, flawed, approachable, and obscure. It is, in our view, significant both for what it communicates (culture under capitalism subtly shapes our attitudes and behaviors in ways that harm us) and how it communicates it (with grace, humor, and urgency).

OK. Lest this fully veer into uncomfortable Stan territory, let’s wrap things up.

***

The talk was followed by an unfortunately short discussion between RFQ, Samiha Meem, and Prof. Magdalena Olszanowski - a scholar of electronic media and feminist internet history who teaches in the Communications department at Concordia University. The back-and-forth between the panelists and RFQ helped to further contextualize the ideas put forward during the talk, but faltered a little. Jia Tolentina, Durga Chew-Bose, the impact of Tumblr, the complicated routes by which online public figures make money, Mark Fisher, and Hype House were all touched on and haltingly discussed. That there was only one microphone between the three discussants and a growing awareness that time was running out kept a real conversation from developing.

There was no time for a Q&A and folks were warned that the reception could not accommodate everyone, but before everyone left RFQ let folks know that there were free posters for the event available at the front of the room. People mobbed the table with little hesitation.

Maybe it’s ironic or entirely fitting that an event centered on the prevalent and misguided belief that the objects you possess define and contribute to who you are concluded with an eager clutch of people clamoring to possess objects that can attest that they were at RFQ’s talk, that they are an RFQ fan, that they are the kind of person who has an RFQ poster. This last complicated, contradictory impulse of many members of the audience is, interestingly, precisely the kind of phenomenon that RFQ tends to interrogate which, in its own strange and spiraling way, suggests that we might need RFQ to investigate the ideological underpinnings that motivate people who attend an RFQ talk. And we, like many others, are here for it in whatever form - TikTok, SubStack, podcast, lecture, AI deathmatch, hologram parade - it might take.

Thanks for writing this! I love the way writers talk about other writers

Thank you so much for your thoughtful review. I really wanted to be there.